Some philosophical theories are so powerful, they shape the way we think and act without us even noticing. Yet understanding the different philosophies can be daunting. Over the past two millennia, there have been dozens of movements, doctrines, and various “isms,” often described in dense and complex academic texts. Here, we’ve broken down six major Western philosophical ideas that still resonate today, from Nietzsche’s nihilism to Platonic metaphysics.

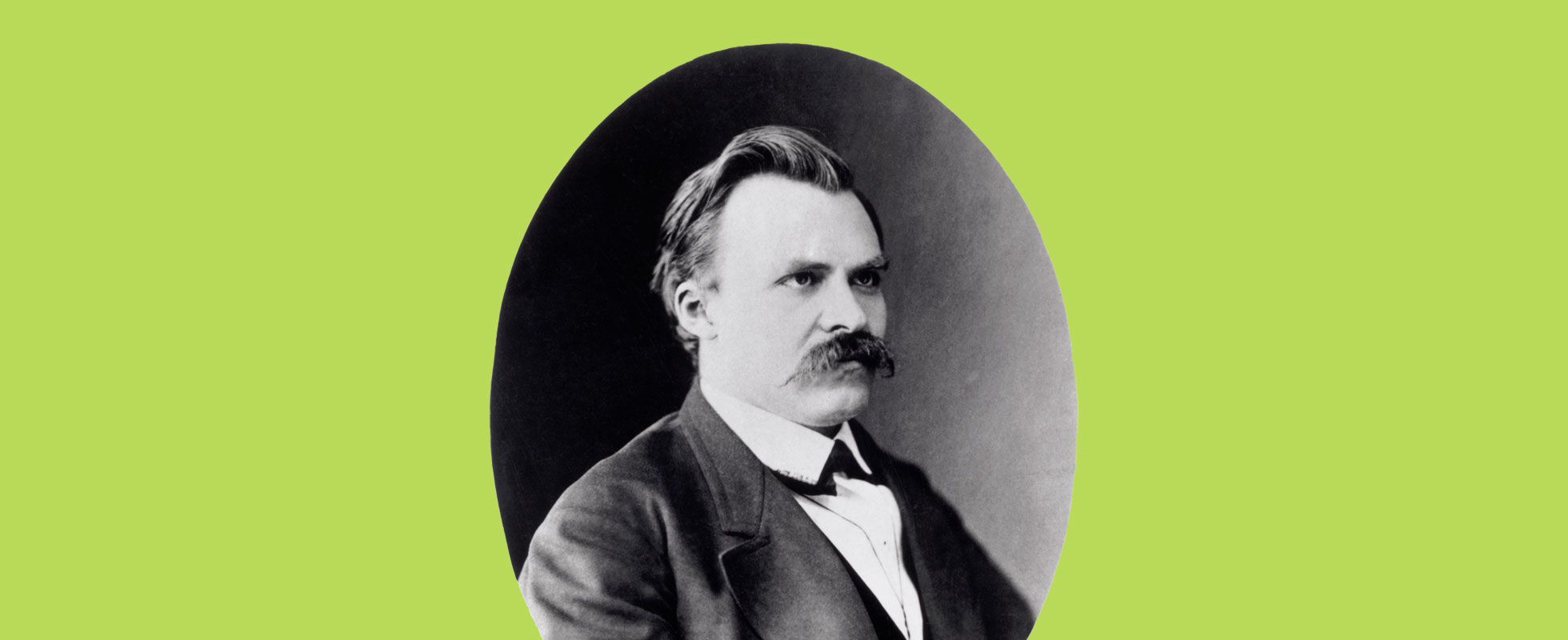

Nietzsche's Nihilism and Übermensch

One of the most misunderstood and misappropriated philosophers, Friedrich Nietszche is most often associated with nihilism — essentially, the rejection of societal values and the belief that life is meaningless. Yet in reality, Nietzsche’s work comes from a place of optimism: The philosopher found himself staring into the headlights of a social crisis, and wanted to find a way to help humanity through it.

In his 1882 book The Gay Science, Nietzsche famously wrote that “God is dead.” But the philosopher wasn’t advocating for atheism; he was pointing out that Christianity had lost much of its power in Europe. By the late 19th century, science and scholarship had chipped away at people’s faith. Nietzsche saw two possible outcomes: Either people would despair into nihilism and drift away from any moral principles, or they would try to find new “religious” convictions elsewhere, namely in mass political movements such as communism or fascism.

Nietszche shuddered at the thought of the second option, which would later become frighteningly real in his home country of Germany. He argued that people had no choice but to forge ahead through nihilism instead. But rather than embrace a meaningless life — and fall into corrosive despair — he offered a solution: the Übermensch, or “superman,” a concept he championed in his 1883 book Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

In Nietszche’s philosophy, the Übermensch is a person who rises above the conventional notions of morality and creates new values that embrace the beauty and suffering of existence. “Our way is upward, from the species across to the super-species,” he wrote, maintaining that this new moral code could guide people to a higher purpose.

Nietszche felt the ideal human was within reach of any person who worked for and achieved self-mastery. He was also no fan of Christianity, and believed people could only reach their full potential as individuals after eschewing the conventional herd morality of religion. He wondered, "Is man one of God's blunders? Or is God one of man's blunders?”

Though it’s often misunderstood, Nietszche’s philosophy was hardly just the stuff of gloom and doom, and indeed aimed to be life-affirming. In fact, alternate translations of his book The Gay Science call it The Joyful Wisdom.

Sartre’s Existentialism

French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre’s declaration that “existence precedes essence” forms the very starting point of existentialism. This complex philosophy suggests that our values, identity, and purpose on Earth are not inherent or predetermined by some cosmic blueprint, but rather created by ourselves via the choices we make through our own free will.

Sartre argued that “man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does.” As he put it, "There is no traced-out path to lead man to his salvation; he must constantly invent his own path.”

This belief in self-determination was furthered by Sartre's contemporaries Simone de Beauvoir and Albert Camus, who were frequently known to meet in Parisian cafés throughout the mid-20th century. Camus delved deeper into the concept of absurdity, believing it was inherently absurd to search for meaning in a meaningless world; de Beauvoir, meanwhile, penned the The Second Sex, a seminal work of feminist literature that exposed society’s history of gender inequality.

Though existentialist philosophy has taken many different forms through the years, at its core it tackles one difficult and fundamental question: What is the meaning of life? This school of thought doesn’t answer the question, but asks us to consider it, by exploring the purpose and value of human existence. The existentialists argue it is up to each of us to define ourselves and find our own individual meaning. As Sartre wrote, “Life is nothing until it is lived… the value of it is nothing else but the sense that you choose."

Rousseau’s General Will

An influential figure of Europe’s Enlightenment era, Jean Jacques Rousseau never viewed himself as a mere philosopher; he was also a musician, playwright, and composer. But his political philosophy of the “general will” — a collective will that aims at the common good — had a more lasting influence than any aria, shaping governments across the world.

In the 1760s, Rousseau was in his 50s and monarchs were still ruling Europe. But the Genevan thinker believed that kings and queens had no divine right to legislate the masses. He outlined these beliefs in his 1762 book The Social Contract, which envisioned a world governed by free and equal people. "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains," Rousseau wrote. When the book was promptly banned in France, it proved the philosopher’s central thesis: Individual freedom was easily hampered by the authority of the state.

In The Social Contract, Rousseau spent a lot of time exploring the contradictions of freedom. Society was expanding at the time, and people were growing more dependent on others for survival. A strong state was necessary to help ensure equality and justice — but how could you build strong political institutions, endowed with the power and authority needed to maintain order, while still protecting individual freedoms?

Rousseau’s solution was his theory of “general will.” He believed that under a monarchy or dictatorship, laws routinely impinged on freedoms because the rulers knew or cared little about what was best for the common people. He argued that in order to protect the freedoms of the public, laws had to be determined by the collective will (or general will) of the citizenry, based on the common good. And the best tool to interpret the general will was democracy — a state governed by the people.

Rousseau believed that a democratic system was the only way to serve the collective will, but he admitted that this form of government was difficult to pull off in practicality. He quipped, "If there were a nation of Gods, it would govern itself democratically. A government so perfect is not suited to men." Nonetheless, his political theory is credited with sparking the French Revolution and possibly inspiring the Founding Fathers of the United States. Today, many of society’s political issues continue to revolve around the fundamental tension Rousseau identified: How best to balance personal freedoms with state power?

Schopenhauer’s Theory of Aesthetics

German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer was a famous curmudgeon, a wild-haired pessimist who notably helped introduce Western intellectuals to Indian philosophy in the 19th century. His writings, however, would forever change the way we think about art.

Before Schopenhauer, most artwork — from music to painting to dance — was considered a frivolous diversion, akin to a decorative craft, rather than an expression of creative genius or a person’s innermost feelings. Schopenhauer helped change those attitudes with his theory about the human will. The essence of his philosophy is that we are held captive by our wills — our strivings, desires, and urges — and are thus doomed to suffer. He observed, "A man can surely do what he wills to do, but cannot determine what he wills.”

One way to escape this suffering, Schopenhauer argued, was through aesthetic experiences. He believed art can function as a quasi-religious experience, freeing us from the suffering of our own desires and serving as a source of inspiration. In his essay On the Suffering of the World, Schopenhauer wrote, "The true work of art leads us from that which exists only once and never again, i.e. the individual, to that which exists perpetually and time and time again in innumerable manifestations, the pure form or Idea."

Schopenhauer argued that great art was the product not of mere craftsmen, but of genius. Naturally, a lot of artists were fans of Schopenhauer’s thoughts on aesthetics. Composer Richard Wagner, novelist Leo Tolstoy, and reams of other creatives trumpeted his work, which elevated art to a higher plane. Tolstoy himself stated, "Art lifts man from his personal life into the universal life."

Thanks to Schopenhauer’s theories, artists and artwork started being lauded as vital and necessary to the health of society. A canon of famous masterpieces was created, as people viewed creators with a growing God-like reverence. This attitude toward art helped define the 19th-century Romanticism movement, and it still persists today.

Descartes’ Dualism and Rationalism

“I think, therefore I am.” More than a catchy quote, the famous declaration by the French philosopher René Descartes continues to shape the way we think about knowledge. And it all started in the 17th century with Descartes’ method of “radical doubt,” which he saw as the only way to be certain that the things we think we know are in fact undeniable truths.

At the time, it was a common belief that we acquire knowledge through senses such as touch and sight. The skeptical Descartes, however, pointed out the senses could be deceiving. (A person, after all, could be hallucinating or dreaming.) That begged the question: If the senses aren’t trustworthy, what’s stopping us from doubting everything, including our own existence? Descartes eventually concluded, “Cogito, ergo sum” — “I think, therefore I am.” The fact that you can doubt your own existence, the philosopher said, is proof that you exist.

Descartes argued that the conscious mind is not part of the senses, or the physical world at all, but that the mind and body are distinct and separate entities. He said, "When I was examining what I was, I realized that I could pretend that I had no body… but I could not pretend in the same way that I did not exist." This theory, dubbed Cartesian dualism, was widely adopted by thinkers across the West.

To Descartes, trusting the mind was of the utmost importance, as the philosopher valued human logic and reason above all else. One of the founders of modern rationalism, he believed knowledge could only be attained by individual reason (versus, say, faith or experience), and that answers to the most perplexing questions could be found simply by exercising doubt and critical thought. His idea that beliefs must be methodically tested by logic and skepticism led to a flourishing of scientific thought, laying the groundwork for Enlightenment thinking and debate throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.

Plato’s Theory of Forms

It’s easy to close our eyes and imagine a perfect circle, but if we open our eyes and try to draw one, it’s a very different story. That’s Plato’s metaphysics in a nutshell: While most of us can conceive of a perfect circle, none of us can recreate one.

The ancient Greek philosopher posited that every object on Earth is imperfect (like the circle we draw) but possesses an ideal “form” or “essence” (like the perfect circle in our mind). While forms are unchangeable, pure, and ideal, the objects on Earth are mere “shadows” — or blemished imitations — of those forms.

While it may sound overly abstract, Plato’s Theory of Forms proved to be a useful way to think about the world. Recognizing a thing’s ideal form can help us understand how it falls short in reality, and thus what needs to be changed or improved. In other words, the ideal can serve as a goal to better both society and ourselves. As Plato said, “For a man to conquer himself is the first and noblest of all victories.”

For example, replace the idea of the perfect circle with the perfect justice system. Many people believe that a truly fair, ideal system of justice exists, but that the current system falls short of that vision. Our belief that a standard, fixed, and ideal justice system is out there as a goal to aim toward is fundamentally Platonic.

Though essentialism — the belief that all things possess inherent, discoverable qualities — has long been controversial, Plato’s Theory of Forms helped shape Western philosophy. His work influenced the theories of many thinkers over the following centuries who built on, or challenged, Plato’s ideas, forming schools of thought that continue to impact how we understand the nature of our reality, and our own existence in the world.

Photo credit: Bettmann via Getty Images