Mary Ann Evans, later known by her pen name, George Eliot, was born in 1819 on the grounds of the Arbury Hall Estate in Warwickshire, England, where her father worked. She had a good education in a staunchly religious environment, learning French, Italian, and Latin, and studying the Bible. The path of Eliot’s began to change when she met a ribbon manufacturer, Charles Bray, who was a self-taught freethinker and radical. She began to question everything, including her religious beliefs, which greatly annoyed her father. But her course had been set, and soon she began to write — and what a writer she was.

In 1859, her first complete novel, Adam Bede, was published to instant critical success — and much speculation as to who this George Eliot fellow could be. The novel also introduced a new form of realism and psychological analysis into modern fiction, something that would be further developed in her later novels, such as The Mill on the Floss, Silas Marner, Middlemarch, and Daniel Deronda. Her novel Middlemarch, A Study of Provincial Life initially received mixed reviews, but literary critics of the 20th century reevaluated the novel, hailing Eliot’s use of realism in historical events, her examination of rural society, and the themes of political reform, education, and the status of women. Middlemarch is now widely considered her greatest work and one of the greatest novels in the English language.

Today, George Eliot is considered one of the most important Western writers of all time. But there are aspects of her life and work that are not so well known, ranging from her literary accomplishments beyond fiction-writing, to what was seen at the time as a scandalous love life.

She had more than one reason to use a pen name

Eliot decided to write under a pseudonym in 1857. She wanted to avoid the stereotype of women’s writing at the time, which was considered lighthearted and frivolous. She also wanted to shield herself from scandal, as she was an unmarried woman living with a married man. She told her publisher that the pen name would serve as “a tub to throw to the whale in case of curious enquiries.” It is likely that she chose the name George in tribute to her lover, George Henry Lewes. She chose Eliot because she found it to be “a good, mouth-filling, easily pronounced word.”

Charles Dickens had his suspicions about George Eliot’s true gender

Charles Dickens wrote a letter to Eliot in 1858 in praise of her first published work, Scenes of Clerical Life. Dickens began with “My Dear Sir,” but soon respectfully explained his doubts regarding her gender: “I have observed what seem to me to be such womanly touches, in those moving fictions, that the assurance on the title-page is insufficient to satisfy me, even now.” In 1859, after the publication of her first complete novel, Adam Bede, Eliot revealed her true identity — partly in response to a number of imposters who were claiming authorship. This prompted Dickens to write her another letter in praise of her work, this time addressed to “My Dear Madam.” Despite revealing her true identity, Eliot continued to publish under her pen name.

She didn’t only write novels

Eliot’s greatest literary achievements were her novels, but she wrote more than fiction. Her first prominent literary work was an English translation of David Strauss’ The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined — a controversial work that questioned the literal truth of biblical texts. The Earl of Shaftesbury called Eliot’s translation “the most pestilential book ever vomited out of the jaws of hell.” Along with her various translations, Eliot wrote for and edited the left-wing journal The Westminster Review. She also published two volumes of poetry, but her poems never achieved the same success as her novels.

Her romantic life was scandalous in its day

Eliot’s lover, George Henry Lewes, was a man of many talents: dramatist, novelist, biographer, literary critic, philosopher, scientist, and editor. But today he is remembered primarily for his decades-long relationship with the famous author. Lewes was a married man and couldn’t obtain an official divorce, but he and Eliot lived openly together until his death in 1878. It was a scandal at the time, and Eliot became estranged from many family members and friends, but it never tore the couple apart. After moving to Germany with Lewes in 1854, Evans wrote to a friend explaining her views on the relationship: “Light and easily broken ties are what I neither desire theoretically nor could live for practically. Women who are satisfied with such ties do not act as I have done — they obtain what they desire and are still invited to dinner.”

She was a harsh critic of other women authors

Eliot used a pen name partly to avoid being pigeonholed among what she saw as the “less serious” female authors of her day. She was not afraid of criticizing these authors, and did so very publicly in her essay “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists.” She described these works as having a “particular quality of silliness that predominates in them — the frothy, the prosy, the pious, or the pedantic.” She made it very clear, however, that “fiction is a department of literature in which women can, after their kind, fully equal men.”

Virginia Woolf and Vincent van Gogh were both fans

Virginia Woolf greatly admired Eliot, both for her writing and the way she lived her life. She called Middlemarch a “magnificent book which with all its imperfections is one of the few English novels written for grown-up people.” Vincent van Gogh was also inspired by Eliot, who, alongside Charles Dickens, was one of his favorite authors, in part due to her vibrant depictions of provincial life. In a letter to his brother, van Gogh explained how Eliot’s novel Felix Holt, the Radical, was “a book that touched me deeply, and it will no doubt have the same effect on you.” He sent his brother a copy of the book along with the letter.

She gave us a few modern words and phrases

Eliot coined, or at least popularized, a number of words and phrases that we use today. Among them are the words “chintzy” (meaning gaudy or trashy), “floppy,” “lampshade,” and “lunchtime.” She was also the earliest person to have used “pop,” short for “popular,” in relation to “pop music.” She wrote in a letter, “There is too much ‘Pop.’ for the thorough enjoyment of chamber music they give.”

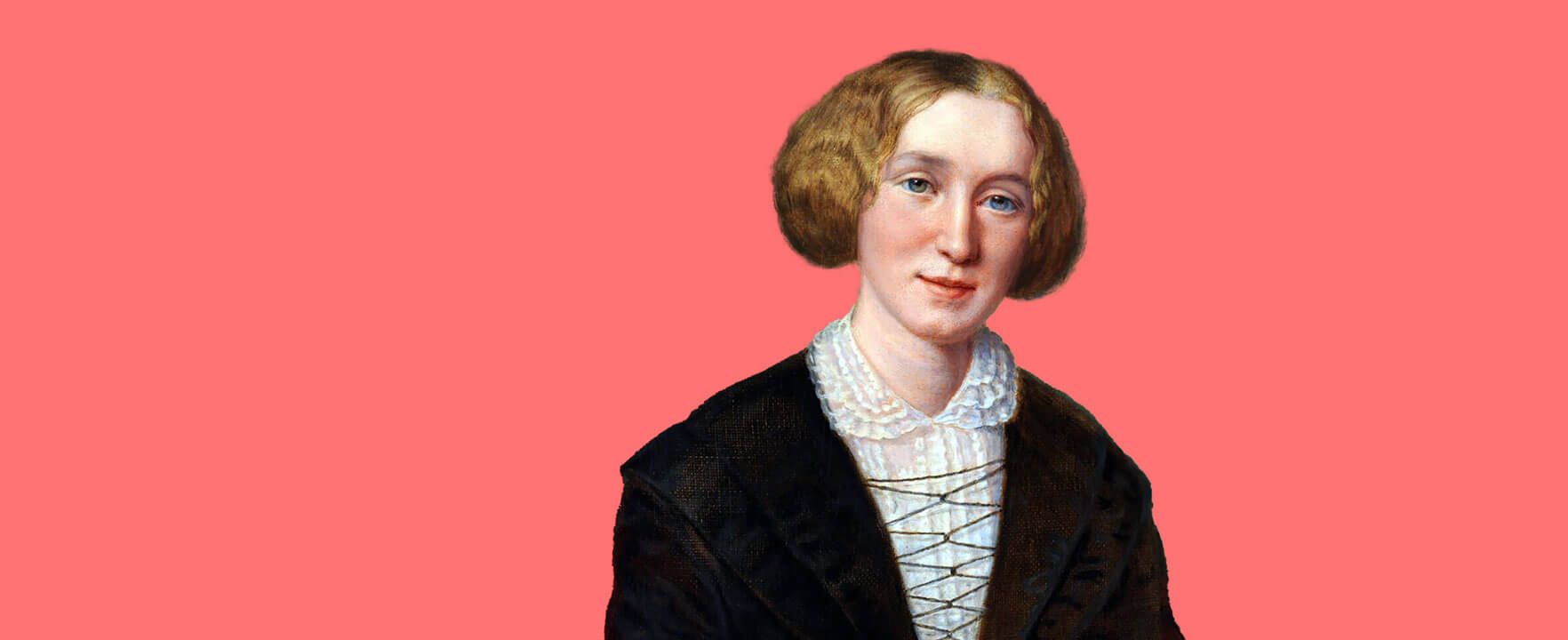

Featured image credit: Pictorial Press Ltd/ Alamy Stock Photo